[info]We all start our lives with sensory experiences. The aspects of perceived experience are stored in long-term memory and form ‘perceptual symbols files’, to be used later for reference.[/info]

From vision, visual images are acquired. From hearing, auditory perceptual symbols are stored. From olfaction, ‘smell pictures’ are received. From gustation, a file of ‘tastes’ is filled in. From touch, perceptual symbols for textures, pressure and temperatures are formed. And from proprioception, perceptual symbols for limb movements and body positions are mapped.

With the appearance of language, the concept formation system changes. Any verbal word generalizes. It is like a folder that contains all the information about a class of objects, events, situations. These ‘folders’ categorise the world, bringing order and providing the child with easily accessible ‘slots’ into which they can sort the incoming information. Non-autistic children learn to form concepts. The information that doesn’t fit the concepts is screened out as irrelevant. The concepts become filters through which all sensory experiences are filtered and organised into classes, groups and types. Children learn to get meaning from things, people and events, and to go beyond what’s perceptually available. They unite things (not identical but serving the same function) under the same label, e.g., it doesn’t mean whether a toothbrush is pink or blue – it’s still a toothbrush. Concepts bring order, helping to put ‘bits and pieces’ of sensory impressions to form a cohesive picture. The outside world becomes conceptualised, represented and expressed in words that can be easily operated to create new ideas. Cognitive processes become more efficient and rapid because they allow them to ‘jump’ from a very few perceptual details to conceptual conclusions.

In contrast, many autistic children perceive everything without filtration and selection. That is why they often have difficulty moving from sensory patterns (literal interpretation) to understanding of functions and forming verbal concepts. For those who have difficulty easily forming the ‘verbal concepts’ the world consists of unconnected and incomprehensible experiences. (An interesting theoretical explanation of this phenomenon has been put forward by Prof. Allan Snyder and colleagues (2004): autism is the state of delayed acquisition of concepts.)

Even at the pre-verbal stage, autistic perceptual symbols (‘sensory words’) differ from non-autistic ones. The symbol formation process in autism often depends on the sensory channel(s) the child uses, or which particular channel is ‘on-line’ at the moment. As a result of differences in perception, the information about objects, people and events is not organized into a coherent picture. That is why perceptual images (of any sensory modality) are not established into categories and remain as separate entities.

However, this doesn’t mean that they remain stuck at the very early stage of development (before acquiring verbal concepts/language). They do develop but ‘via a different route. With the sensory-based system being dominant, the sensory impressions they store in their memory become templates for recognition and identification of things, people, events (Bogdashina 2004). Thus, different perceptual systems develop different conceptual systems and result in different intelligence systems.

The content of a linguistic word doesn’t resemble its referent. In contrast, perceptual ‘words’ refer clearly to specific objects, states, events. Because autistic ‘words’ contain different perceptual content, they are not functionally equivalent to non-autistic concepts. Autistic ‘words’ are very concrete and specific. Instead of storing general meanings of things and events (which is a prerogative of a verbal language) they construct sensory perceptual mental images. They store the experiences (sensory impressions/ templates). Once a perceptual image is stored in long-term memory, it becomes a representation of physical input. It becomes a symbol for a certain referent and can represent the object in its absence. It means that if a person has stored ‘a ball’ by smell, then if it doesn’t have the same smell as the one he stored for the first time, it cannot be identified as ‘a ball’, even if it looks like a ball, sounds like a ball, etc. To be identified, the thing should ‘feel right’, i.e. be exactly the same as in the first experience.

It results in autistic hyperselectivity and a lack of generalisation: the item to be recognised must be exactly the same as the one that was stored the first time. For those who have difficulty easily forming these ‘verbal concepts’ the world consists of unconnected and incomprehensible experiences.

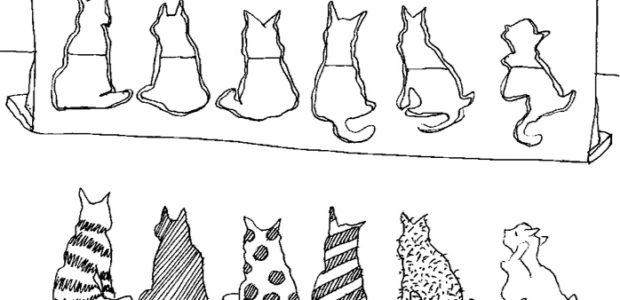

Remembering ‘literally’ means that everything is ‘the’ something, e.g., different breeds, colours, sizes of cats make each of these pets a different ‘sensory word’ as they are perceptually different. Some autistic children cannot find any association between things that change places. They are able to identify a picture of a cat in the book as a cat, but a cat outside the house cannot be identified.

Paradoxically, sometimes different stimuli may ‘feel’ the same and become ‘unconventional personal synonyms’. For example, to Alex some words have a similar shape, pattern or rhythms without being similar in meaning, so the words ‘Oliver’ and ‘cinema’ have the same feel and seem similar to him.

It is important to teach the same concepts with different items of the same class of objects (not the same pictures/objects all the time), different places, and with different people. When this is achieved, concepts can help to prevent sensory overload and decrease confusion. Providing a ‘name’ for the chaotic environment can help the child to figure out what is going on.

References

Bogdashina, O. (2004) Communication Issues in Autism. Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Snyder, A., Bossomaier, T., Mitchell, J.D. (2004) ‘Concept formation.’ Proceedings of the Royal Society of London, 266.

Written by Olga Bogdashina on behalf of Integrated Treatment Services